Qi (China)

Translated and edited by

John Voigt

Qi is a concept commonly found in Chinese philosophy, Daoism, and traditional Chinese medicine. The thinkers of the Spring and Autumn Period (Cir. 771 to 476 BCE) and the Warring States Period (453-403 BCE) thought of qi as the basic element in the composition of all things in heaven and earth, and also that it was the cause and effect of everything in the universe. In addition it was considered a dynamic energetic substance having the characteristics of being able to freely and spontaneously circulate (flow) from place to place.[1]

Qi is the energy or power of vitality which is

possessed by mankind and all living creatures.

Everything in the universe is the result of the

operation and changes of qi. Chinese medicine

believes that qi is the body's first line of

defense, gathered within the body to protect the

five organs, as well as circulated and distributed on the surface

of the skin to help create a barrier for the

prevention of the invasion of unhealthy [i.e., "xie"],[2]

here meaning the external influences that bring

about disease.

as well as circulated and distributed on the surface

of the skin to help create a barrier for the

prevention of the invasion of unhealthy [i.e., "xie"],[2]

here meaning the external influences that bring

about disease.

Evolution of the Character for Qi

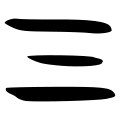

Oracle bone script - circa late 2nd millennium BCE.

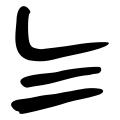

Bronze script - late 2nd millennium BCE.

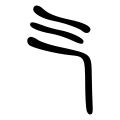

Large Seal script – late 1st millennium BCE.

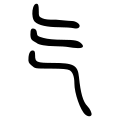

Small Seal script – late 1st millennium BCE.

Traditional Chinese Character – became the standard script beginning circa 500 CE., and continued so until the mid-20th century in mainland China. It still is the standard script as used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau today.

Simple (Modern) Chinese Character – became the standard script in mainland China in the 1950s and 1960s. It is also used world wide.

A note about the above confusing datings: The concept of an orderly evolution of scripts, each one suddenly invented suddenly and completely displacing the previous one, has been conclusively demonstrated to be fiction by the archaeological finds and scholarly research of the later 20th and early 21st centuries. The gradual evolution and the coexistence of two or more scripts (during the same time period) was more often the case. See en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_characters

Chinese Characters

气 – the Simple character for Qi, in use from the mid-20th century, means among many other things, "gas" and "air."

氣 – the Traditional character for Qi, in use from

the 5th century, is now occasionally

being found in usage in modern mainland China to

represent its older more philosophical, religious

meanings, such as the "vital energy" (or "breath")

within all living things, and that which permeates

and supports the entire universe. By extension the

word Qi may also represent the consciousness within

all things, and possibly the "soul," or "spirit";

and even "the external activities of God."

Traditional script, along with its meanings, is

still used in Taiwan and in other places.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki It was translated into English as "Chi," especially

before the 1960s.

It was translated into English as "Chi," especially

before the 1960s.

The Origin and Historical Development of the Word Qi

The word qi originally meant "clouds," (and the

"mist" or "vapor" that rises to form clouds). Then

"Then "breathing," then the vital energy of

breathing." Then "rice." The meaning of the word was

quickly extended to encompass such things as

"weather" (sky qi), "climate" (seasonal qi),

"solar terms" (a 24 seasonal calendar), as well as "smell" (i.e.,

qi taste), "atmosphere" (wind qi). Also ren qi ("a

person's qi" –人气) meaning "personality"

–"popularity" – and "character."[3]

(a 24 seasonal calendar), as well as "smell" (i.e.,

qi taste), "atmosphere" (wind qi). Also ren qi ("a

person's qi" –人气) meaning "personality"

–"popularity" – and "character."[3]

Different characters were developed to represent qi, such as 炁 used in Daoist writings; and 餼 ("a portion of rice," "a grain sacrifice for animals," "a sacrificial victim"). After the Tang Dynasty (10th century) the character for qi had achieved its standard form: 氣 and remained so for the next ten centuries.

However, after the Song Dynasty (960-1279), Daoist thinkers used the old character "炁"[4] for qi to represent innate primordial qi and the everlasting unbounded heavens (Wuji); and the character 氣 to represent acquired qi (vital breath) and the Supreme Ultimate (Taiji). Nevertheless, apart from Daoist (Taoist) literature, qi was most often written as 氣.

Chinese Medicine

Qi is a basic working concept in traditional

Chinese medicine. Qi is the fundamental thing that

maintains the activities of life. Qi is stored

within the blood, and can move outside the blood

vessels. It can accumulate in the acupuncture

points, as well as in the bones. Qi can maintain,

defend, and restore the functions of the internal

organs, and bodily systems, as well as for the skin,

flesh, and muscles. It can be used to repair tissues

and organs, and resist the pathogenic unhealthy

influences that cause disease. The qi used in

support of the body's functions is called Primary

(Yuan) Qi; the qi that flows outside the meridians

is called

Defensive (Wei) Qi.

The qi that is distributed in the meridians (i.e., the energy "channels" or "vessels" - jing luo - 经络) is called Meridian qi.

The qi that is distributed in the inner organs is called organ or body qi.[5]

In like manner there is heart qi, and stomach qi, and so forth.

The qi concentrated in the area of the chest is called Middle or Gathering qi (Zong qi).

The qi gathered in the lower abdomen (the dantian) is called Primal or Vital qi (Yuan qi).

The qi that brings about normal health is called Righteous qi (Zheng qi).

The qi that brings about illness is called "Evil qi" (Xie qi). Such pathogenic qi can be brought about by leading an abnormal life style.

The nourishing energy that comes from food and maintains the functions of the body is called Grain or Food qi (Gu qi).

The qi that generates the normal functioning of the inner organs, and [for example] causes the growth of hair is called Real or Genuine qi (Zhen qi).

To have an active vital qi means you will have an active personality.

You possess qi because you have a spirit (Shen).[6] You have a spirit because you possess qi.

No qi means no spirit; less qi means less spirit; plenty of qi means plenty of spirit.

In the acupuncture points, qi functions as an action in progress, either moving through the points, or temporarily stopping and staying there. Acupuncture points are also known as "qi acupoints."

The qi in the meridians is generated by the inner organs. The qi of the inner organs originates from the food in the digestive organs (Stomach and Spleen), and from the respiratory system of the lungs.

Acupuncture and moxibustion by regulating the qi in the acupuncture points adjust and harmonize the flow of qi in the meridians and internal organs. Many different kinds of medications will also regulate the qi of the inner organs.

Qi can be stored in the

five zang organs (yin organs), - or be concealed in the marrow of

the bones for future use.

(yin organs), - or be concealed in the marrow of

the bones for future use.

Qi can be turned into Jing (the essence of life).[7]

Jing can be, become, or behave as Qi.

Qi can be turned into Shen (Spirit).[6]

Daoists control their Shen to collect Qi in order to store their Jing (sexual essence) to use in meditational visualizations in order to delay aging.

The movement and behavior of qi is influenced by the weather, the seven emotions (joy, anger, anxiety, worry, grief, fear, and fright), the six sensual desires (that arise from seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, feeling, and thinking). Diet (hunger) and sexuality (lust) especially affect qi's behavior. The result of all these things can be health or disease.

A doctor trained in traditional Chinese medical science will adjust qi and harmonize its flow [in the body and mind].

Qi is divided into yin and yang. Both yin and

yang qi run through the organs and their

corresponding energy channels (meridians). The solid

(Zang) organs (i.e., Heart, Liver, Spleen, Lung,

Kidney) store qi. The hollow (Fu) organs main

purpose is to process food. They are the Small

Intestine, Large Intestine, Gall Bladder, Urinary

Bladder, Stomach, and the Three Burners. [Note: The

"Three Burners" (San Jiao 三焦) describe the

functions of physical organs, and not the organs

themselves. The upper burner relates to the organs

above the diaphragm, those concerned with

respiration. The middle burner relates to the organs

in the middle of the torso, those concerned with

digestion. The lower burner relates to the organs

in the lower abdomen, those concerned with sexual

reproduction and excretion. See:

lieske.com/channels/5e-sanjiao.htm.]

Modern Interpretations

The Theory of Blood Circulation Resonance states that within all blood circulation there is

the phenomenon of resonance. Blood vessels have

their own specific resonance frequencies; organs and

acupuncture points also have their own specific

resonance frequencies. Because of coupling

vibration, organs, acupuncture points, and arteries

share in the harmonization of these frequencies.

states that within all blood circulation there is

the phenomenon of resonance. Blood vessels have

their own specific resonance frequencies; organs and

acupuncture points also have their own specific

resonance frequencies. Because of coupling

vibration, organs, acupuncture points, and arteries

share in the harmonization of these frequencies.

Human organ systems have their own frequencies; and organs with the same harmonic resonance are classified in the same category, therefore naturally visceral and meridian relationships take place. The five internal solid organs and their meridians belong to the low frequency group, which is yin. The six hollow organs and their meridians, belonging to high-frequency group, which is yang.

From the theory of resonance, "qi" is the

manifestation of the pressure energy exerted by the

heart. When the organ systems lack this pressure,

their qi is insufficient. When the tiny arteries in

the organs are contracted and then opened, there is

not enough power for the blood to properly enter

into the smaller blood vessels. Due to the lack of

qi and blood, the organ systems will be deprived of

both oxygen and the nourishment derived from food.

Metabolic waste material will accumulate in the

body. The immune system will suffer, and in time

bodily illness and disease can be the result. [Wang

Weigong. Qi Movement. Taiwan: Chunk Culture

Press. ISBN9867975502.]

[See also: zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/血液循環共振理論.]

Daoism and Qi (道教的氣)

道教內丹研修者鄧善陽對「氣」的記述:

On Seeing Qi: Yuan Qi. -元气- (Original - Primal – Fundamental Qi –元气) can be seen in deep states of meditation. In some cases, it can even be seen when you open your eyes.

(Chinese: 看得見的氣:先天氣,在靜坐時可以看到。在某種情況,張開眼睛時亦可看見。References: 鄧豐洲. 臺中市: 白象文化. 2017年1月: 45. ISBN 9789863584490.)

Qi is like: warm pearls, sweet nectar, hot dumplings, a spring breeze, an magical generative mist, electric waves, aliveness in a hot moist jungle, ripples of electricity, the smell of wood burning in a fireplace, clouds covering a mountain, stars twinkling in a dark nighttime sky, flashing lightening, sweet smelling perfume, spices, a stick of burning incense; the smell of a healthy baby or of a young girl.

(Chinese: 氣的禮讚:氣如熱珠、甘露、氣團、春風、氤氳、電波、輕煙、山嵐、星辰、電光、罊香。References: 鄧豐洲. 臺中市: 白象文化. 2017年1月: 47. ISBN 9789863584490.)

Both quotes by

Deng Fengzhou (鄧豐洲) from: 鄧豐洲.《鄧善陽内丹學札記詩集》("Tangshan Collection of Posthumous Books," January 2017: 45.)

from: 鄧豐洲.《鄧善陽内丹學札記詩集》("Tangshan Collection of Posthumous Books," January 2017: 45.)

Editor's Comments

This entry is a translation of

氣 (中國). It was last accessed on January 7, 2018. Additional

footnotes and editorial comments were added by the

editor of qi-encylopedia.com.

It was last accessed on January 7, 2018. Additional

footnotes and editorial comments were added by the

editor of qi-encylopedia.com.

Text used under the

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/ and the GNU Free Documentation License:

www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html

and the GNU Free Documentation License:

www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html Additional terms may apply. See

Terms of Use

Additional terms may apply. See

Terms of Use for details.

for details.

Footnotes:

[1]^

Early Chinese scholars suggested that besides being

the fundamental force in the creation of all things,

qi also acts as an intermediary between all things

in the universe, making it possible for everything

to coherently and orderly interact with each other.

For example, mankind and nature harmoniously

cooperating with each other in such things as

practicing a sensible nature sustaining ecology. Or

in the way the movements of the sun and moon always

are related to each other. These things are possible

because of the

omnipresence of qi.

[2]^ Unhealthy – Xie - 邪, pronounced shay (rising tone). In Pinyin it is xié. The dictionary meanings are turbid, pathogenic, evil; the unhealthy energetic imbalances that lead to disease. It is in contrast to the body's vital energy (Zheng Qi) which resists disease.

[3]^

Qi has many more different meanings especially when

it is combined with other words.

www.chinesetools.eu/chinese-dictionary

The word Qi standing alone is not properly or authentically defined as "Energy." In as far as "energy" is concerned, qi will most often only mean "vital energy" or "bio-electric energy" as found in traditional Chinese medicine and Taijiquan (T'ai Chi Ch'uan).

[4]^

For 炁 as used in Daoist writings see

The Meaning of Qi

[5]^

Organ Qi (Zang and Fu Qi - 脏腑之气). This is the Qi

responsible for the functioning of the internal

organs. The Yang-Fu, hollow bowels, produce Qi and

Blood from food and drink. The Yin-Zang, solid

viscera, store vital substances. Each organ has its

own energy corresponding to one of the Five-Element

energies, which respond to the universal and

environmental energy fields. Thinking, feeling,

metabolism and hormones can influence the Organ Qi.

The solid (Zang) organs transmit yin qi; the hollow

(Fu) organs transmit yang qi.

qi-encyclopedia.com

[6]^ Shen 神. Shen is the source of our instincts and behavior. It has many meanings depending on the context within which it is placed. But the closest concept in western thought is "Spirit." Chinese translation sites also offer besides "spirit": soul, mind, god, deity, supernatural being." Other definitions occasionally may include: personal awareness. Feelings. And thoughts and mental processes, even intelligence. Less often there is consciousness, health, vitality—and the inner sense of being alive. Moving to its Daoist spiritual foundations you may find: Shen - 神 – an internal and external psychic energy; all nonmaterial aspects of human beings and of the universe as a whole.

[7]^

Jing – (精) – "essence." Pronounced Gee(ng) in

a steady high tone. In Chinese Medicine it

represents the purest materials required for life,

such things as genetic factors, DNA, father's sperm

and mother's egg, even the vital qi of heaven. It

may be conceived as a concentrated condensed qi.

More at Elisabeth Rochat de la Vallée.

"Jing, or Essence…"

Further Information on Topics in this Entry:

Xing-Tai Li and Jia Zhao.

The Classification of Qi: An Approach to the

Nature of Qi in TCM - Qi and Bioenergy.

A Bibliography from the

Original 氣 (中國) Entry:

• 秦伯未.《中医入门》. 北京: 人民卫生出版社. 1959年.

• 罗石标, 也谈气[J],中医杂志,1962年, (3): 26-27.

• 危北海:《"气"在祖国医学中的应用》[J],《中医杂志》,1961年,(3): 31-33.

• 罗石标:《也谈气[J]》,《中医杂志》,1962年, (3): 26-27.

• 危北海:《答"也谈气"》[J],《中医杂志》,1962年,(3):27-29.

• 危北, "气"在祖国医学中的应用[J],中医杂志,1961年,(3): 31-33.

• 黄坤仪.

人体气场与气. 2008 年7月10日 [2014年7月2日].

2008 年7月10日 [2014年7月2日].

• 秦伯未.《中医入门》. 北京: 人民卫生出版社. 1959年.

• 王唯工.《氣的樂章》. 台灣: 大塊文化出版社. 2002年9月7日. ISBN 9867975502.

•《氣的樂章:氣與經絡的科學解釋, 中醫與人體的和諧之舞,大塊文化出版社,

2009年.

中醫與人體的和諧之舞,大塊文化出版社,

2009年.

• 小野澤精一等編,李慶譯:《氣的思想:中國自然觀和人的觀念的發展》(上海:上海人民出版社, 1990。